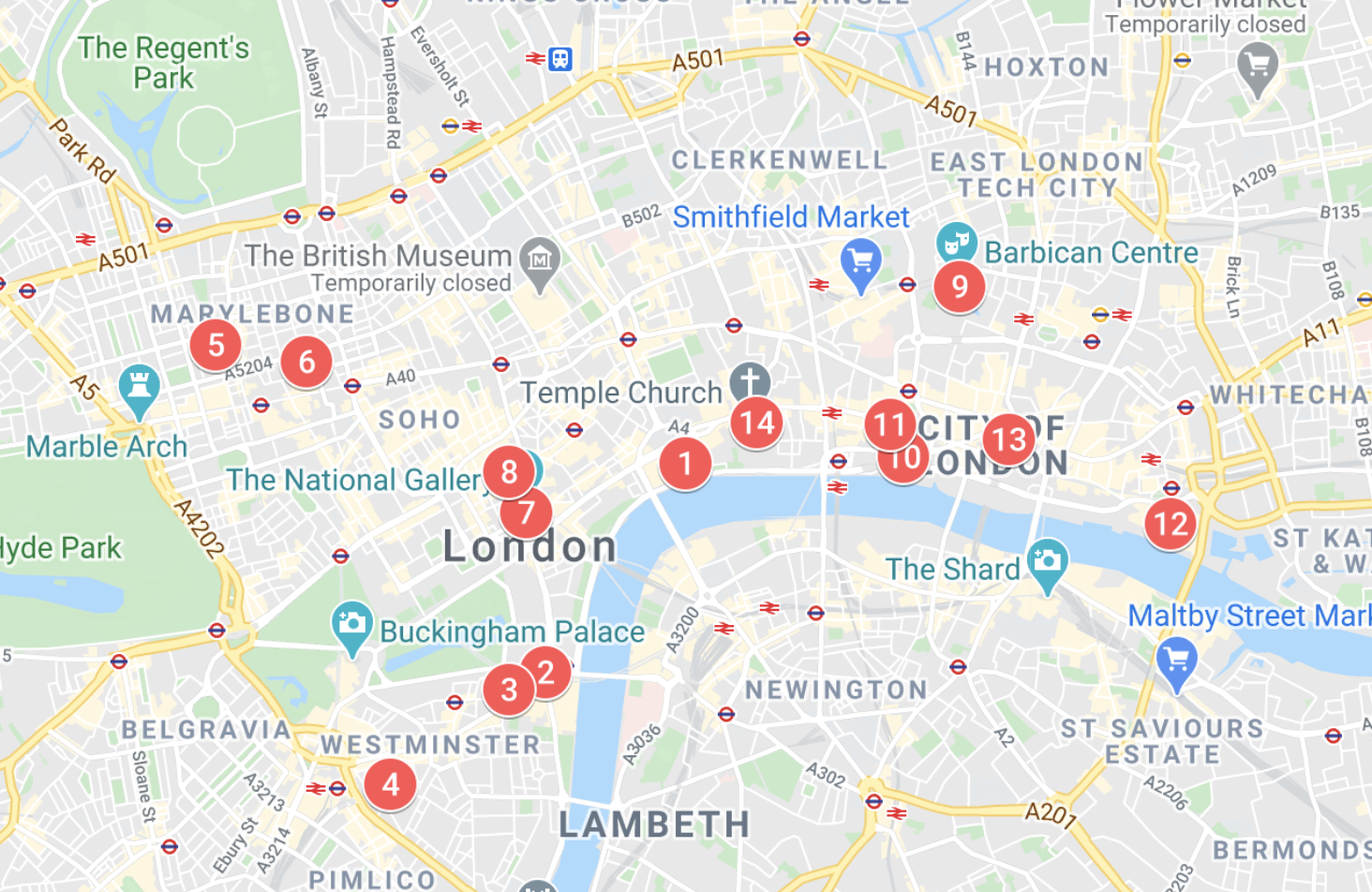

London

January 24 - March 22, 2016

Jesus is Condemned to Death by the Mob

King’s College London Chapel, Strand Campus

Terry Duffy, ‘Victim, No Resurrection?’ 1981

Painted in response to the 1981 UK riots, the message of this piece is just as crucial today: enough is enough and people in power must do more to achieve peace and reconciliation. It challenges people wherever it is shown to greater awareness of the plight of victims. Transcending religious and cultural boundaries, it has become even more pertinent within a global culture of terrorism, suspicion of refugees, and racial and sexual discrimination. This complex, towering piece can be compared to canonical works of protest such as Picasso’s Guernica (1937). In addition to this project, Terry Duffy has been taking this painting on its own journey of Stations of the Cross from Liverpool, where it was painted, to Jerusalem. It has been installed in locations of past and present conflict, including Cape Town, commemorating the end of Apartheid, and Coventry and Dresden, destroyed in World War II.

2. Jesus Takes Up His Cross and Begins His Journey

Parliament Square

Philip Jackson, Mahatma Gandhi, 2015

Jackson took inspiration from a 1931 photograph of Gandhi standing outside Downing Street, where he had come to argue the case for Indian self-governance. Befitting Gandhi’s radically egalitarian vision, the sculpture stands on a modest plinth, humbly approachable by passerby. As Gandhi himself recognized, his dedication to non-violence and the pursuit of truth resonate powerfully with Jesus’ teachings in the Gospels. Jesus was, Gandhi wrote, ‘the highest example of One who wished to give everything, asking nothing in return, and not caring what creed might happen to be professed by the recipient…I believe that He belongs not solely to Christianity, but to the entire world; to all races and people.’ Much as Jesus stood before Pilate, Jackson’s Gandhi looks toward the Houses of Parliament with gentle but steadfast resolve. Both were imprisoned and killed for the principles they espoused. Are we willing to take up the cross for our beliefs?

3. Jesus Falls the First Time

Methodist Central Hall Chapel

James Balmforth, Intersection Point, 2015

The minimalist aesthetic of Balmforth sculpture is deceptively simple. On the one hand, the title seems to demystify the crucifix, rendering it a simple product of geometry: the Intersection Point between two lines. And yet, especially here, in the Chapel of Methodist Central Hall, this cross is not just any cross. Turned to an ‘X,’ it evokes the cross shouldered by Jesus in countless works of art, including the carvings of Eric Gill (Station 4). These pristine white construction beams, crudely singed at the ends, suggest a further meaning. They connote both the stumbling of Christ and the collapse of a building. Combing through the wreckage of Coventry Cathedral after the Blitz, and the World Trade Center after 9-11, survivors looked desperately for symbols of hope. In the simplest of forms—two intersecting pieces of wood or metal—they found the Cross, and with it a promise of redemption.

4. Jesus Meets His Mother

Westminster Cathedral (Catholic)

Eric Gill, Stations of the Cross (Station IV), 1915

Gill’s Stations of the Cross for Westminster Cathedral came at a pivotal time in his spiritual and artistic life. He began work on them just a year after converting from Anglicanism to Catholicism, and they represent one of his first major commissions. As he often did, Gill used himself and those around him as models, representing himself as both Christ and soldier, and using his wife’s hands for Mary. There is little tenderness in this encounter between mother and son. It is as if Jesus has already transcended the earthly plane. He raises his hand in dispassionate benediction, pronouncing in Latin, ‘blessed art thou among women.’ For Gill, who once declared ‘there can be no mysticism without asceticism,’ such reserve increased religious devotion. He also intended his Stations as a support to the downtrodden, as he emphasized in his book of meditations, Social Justice and the Stations of the Cross. However, given what we know today about Gill’s life—and his abusive actions towards those around him, including family—it is important to recognize that images which might bring devotional surety and support to some viewers, may be painful to others

5. Simon of Cyrene Helps Jesus Carry the Cross

The Wallace Collection (Sixteenth-Century Gallery, Wall Case B, Ground Floor)

Panel 20 (bottom row, 2nd from left), Twenty-four Plaques after Albrecht Dürer’s Small Passion Woodcut Series, Limoges, France, c. 1570-1625

Although Simon of Cyrene is mentioned in three Gospels, he remains a mysterious figure. According to Luke, Jesus’ tormentors ‘seized’ Simon and ‘laid the cross on him, and made him carry it behind Jesus’ (23.26). While Simon was later cast as a volunteer and convert, in the Bible his assistance is clearly compelled, at least at first. Simon’s identity is also a matter of dispute. Some interpreters identify him as a Jew, since Cyrene was once home to a significant Jewish population. Others point to his North African birthplace as evidence that Simon was black. Here, an elderly Simon holds the end of the cross. While much of the design is copied from Albrecht Dürer’s 1509 print, from his Small Passion series published in book form in 1511, the artist makes subtle adjustments. Simon looks towards Veronica who offers Jesus assistance voluntarily, as if trying to decide whether to follow her example. What would we do in his position?

6. Veronica Wipes the Face of Jesus

Cavendish Square

Jacob Epstein, Madonna and Child, 1950-52

According to legend, Veronica knelt beside Jesus as he struggled with the cross. After wiping the blood, sweat, and grime from his face her cloth bore the miraculous imprint of Jesus’ face. While Veronica isn’t pictured, Epstein’s Madonna and Child looks unblinkingly towards the events of the Passion. Jesus’ outstretched arms form a cross, while the fabric which surrounds him suggests Veronica’s Sudarium. The garments of the two figures stretch across their bodies like bandages. Maybe it is up to the viewer to play the role of Veronica, lifting a cloth to tend to mother and son. Perhaps Epstein was inspired by the Convent of the Holy Child Jesus, for whom he created this sculpture; or maybe the Royal College of Nursing, which sits at the corner of Cavendish square. He didn’t need to look far to find examples of women prepared to come to the aid of the wounded.

7. Jesus Falls for the Second Time

The National Gallery

Jacopo Bassano, The Way to Calvary, c. 1544-5

This painting nearly constitutes its own Stations of the Cross, evoking several episodes in Jesus’ tormented path to Golgotha, Jesus passes his mother, Mary, who wipes away a tear, Veronica presents her veil, and the women of Jerusalem gather in prayer. A man with a rope tugs Jesus towards the cross in the distance, while another holds his fist aloft, as if already preparing to nail his victim down. Amidst this swirl of activity, Jesus – clad in a strangely pristine pastel robe – serenely falls to the ground. Crammed with figures, the composition should feel hectic. And yet Bassano deploys every feature, from gestures and gazes to billowing fabric, to guide the eye in a smooth, circular sweep. What should be a moment of grimy degradation exudes a tranquil sense of perfection. Even before he dies and rises again, it seems as though Jesus’ has already transcended mortal matter.

8. Jesus Meets the Women of Jerusalem

Notre Dame de France Church (home of the Notre Dame Refugee Centre)

Jean Cocteau, Our Lady’s Chapel, 1959

An acclaimed novelist, poet, and director as well as painter, Cocteau lived a creative and spiritual life of tremendous variation. Of the latter, he wrote, ‘It is excruciating to be an unbeliever with a spirit that is deeply religious.’ At the time he painted the chapel, Cocteau felt a wave of Catholic fervor. Even so, he included a note of ambivalence in a self-portrait beside the cross; his face turned away, eyebrow arched incredulously. The lines in the piece are bold and clear, yet conjure a multivalent, mystical iconography, with tears transforming into hearts, wings, and petals, and eyes doubling as fish and even nipples. Cocteau makes a conscious effort to accentuate the experience of women. Mary’s Annunciation and Assumption take place on either side of the cross. Indeed, only the legs of Jesus appear in the Crucifixion. It is the grief of the women that consume our attention.

9. Jesus Falls the Third Time

The Barbican & St Giles Terrace

G. Roland Biermann, Stations, 2016

Sleek minimalism meets gritty reality. Two crash barriers slice through the air, narrowly missing each another before piercing the wall behind. Jesus’ fall finds a contemporary echo in the everyday tragedy of a car crash. Oil barrels suggest automobiles, but we might also think of olive oil, used in the Bible to anoint priests and cure the sick. Painted fourteen shades of red—suggesting blood that runs, congeals, and quickens anew—the barrels symbolize the Stations of the Cross. Some viewers might find consolation in the symbolism of Holy Blood and Holy Oil. Others will be reminded of blood spilt in the pursuit of fossil fuels. The tensions and binaries in Biermann’s installation—sacred and profane, ancient and modern—suit this site. During the Blitz, the area was devastated—including much of medieval St Giles Cripplegate. Today it houses the Barbican, a symbol of postwar hope and utopian ambition.

10. Jesus is Stripped of His Garments

The Salvation Army International Headquarters

Güler Ates, Sea of Colour, 2016

Güler Ates is best known for her photographs of mysterious figures in shimmering, diaphanous veils, drifting through opulent spaces. Here fabric takes a different form, drawn from donated and discarded children’s and baby clothes, too worn, damaged, or dirty to be used for charity. These castoff clothes offer a haunting reminder of children who have died—sometimes in their mothers’ arms—in journeys to escape conflict. Having suffered displacement from Eastern Turkey herself, the artist feels an acute empathy for refugees, and has created this work with the assistance of women from local refugee groups. In a new way, she returns to a question that emanates throughout her work: can we ever really know the person in front of us? Can we know their pain? Even when Jesus stood naked, stripped of his garments, who among the jeering crowds really knew what he felt?

11. Crucifixion: Jesus is Nailed to the Cross

St Paul’s Cathedral

Bill Viola and Kira Perov, Martyrs (Earth, Air, Fire, Water), 2014

The commission of Martyrs was made possible by a collaboration between St. Paul’s and Tate Modern, located directly across the river. The polyptych is at once a cutting-edge piece of video art and an homage to the themes and imagery of traditional altarpieces. Indeed, Viola hopes these videos become ‘practical objects of traditional contemplation and devotion’. As the video progresses, each of the four performers stoically suffers an assault from the elements—earth, air, fire, water—as if nature itself has determined to test them. The lives of martyrs, writes Viola, ‘exemplify the human capacity to bear pain, hardship, and even death in order to remain faithful to their values, beliefs, and principles. This piece represents ideas of action, fortitude, perseverance, endurance, and sacrifice.’ For Christians, these values are embodied in Jesus’ sacrifice on the cross, but as Perov reminds us: ‘we are all capable of sacrifice.’

12. Jesus Dies on the Cross

The Chapel Royal of St Peter-ad-Vincula, HM Tower of London

Guy Reid, Crucifixion, 2007. Life-size (183 cm x 180 cm), lime wood.

The Romans crucified alleged criminals not only to torture but humiliate them. It was a spectacle, much like the beheadings of purported traitors and heretics in and around the Tower, especially during the 16th century. The thought of Christ’s ignominious execution couldn’t have been far from the minds of martyrs like John Fisher and Thomas More as they faced the executioner’s ax on nearby Tower Hill, or of Anne Boleyn, Catherine Howard, and Jane Grey, executed within the Tower. The bodies of all five are interred in the Chapel. Guy Reid honors this history with an unflinching Christ, who retains his dignity even as he stands utterly naked, pierced by stigmata. Carved from limewood, the work recalls Renaissance sculpture, while retaining a fiercely modern visage. In fact, the face is a self-portrait. ‘I wanted to emphasize Christ’s full and particular humanity,’ says Reid, ‘which I share and we all share.’

13. Jesus is Taken Down from the Cross

St. Stephen, Walbrook

Michael Takeo Magruder, Lamentation for the Forsaken, 2016

As he took his last breath, Jesus cried out ‘My God, My God, why have you forsaken me?’ Resurrection must have felt far away in this moment, and later for the paltry few who remained to tend to his corpse. In this work, Takeo offers a lamentation not only for the forsaken Christ, but others who have felt his acute pain of abandonment. In particular, Takeo evokes the memory of Syrians who have passed away in the present conflict, weaving their names and images into a contemporary Shroud of Turin. The Shroud, of course, is itself an image—an ‘icon’ in Pope Francis’ words—better known by its photographic negative than its actual fabric. Takeo’s digital re-presentation participates in and perpetuates this history of reproduction. But the real miracle isn’t the Shroud itself, it’s our capacity to look into the eyes of the forsaken—and see our Savior.

14. Jesus is Laid in the Tomb

The Temple Church Triforium (upper level)

Leni Diner Dothan, Crude Ashes, 2016

Temple Church was modeled on the circular Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, where Jesus was buried. A former resident of Jerusalem, Dothan responds to the symbolism of Temple Church from an unabashedly personal perspective, as both an Israeli and a mother. In Hebrew, immigration to Israel is called aliyah, ascent, whereas emigration is yerida, descent, a term fraught with pejorative implications. While the Templars built this church as a reminder of their sacred duty to guard Jerusalem and its pilgrims, the church evokes ambivalent feelings for Dothan. What does it mean as a Jew to leave the Holy Land, a homeland about which Jews dreamed for millennia? For Dothan, her ‘descent’ also represents an ‘ascent,’ a choice to pursue her own dreams. She finds a powerful, unexpected metaphor in the entombed Christ, who travels to the depths of hell before rising in resurrection.