Biblical Hebrew Poetry and the Art of Repetition

Jonathan Homrighausen

Happy are those

who do not follow the advice of the wicked,

or take the path that sinners tread,

or sit in the seat of scoffers (Ps 1:1)

The opening verse of the Psalms illustrates a defining feature of biblical Hebrew poetry: repetition and variation, often termed ‘parallelism’ by scholars. If the psalmist’s sole aim was to communicate information, this line would seem redundant: Why mention the wicked, sinners, and scoffers? Are these not the same?

We could simplify the verse to “Happy are those who avoid immoral people.” But this informative-yet-bland solution fails to see the value of repetition in biblical poetry. Each echo paints a different place: the open road, the secret counsel’s closed doors, the fellowship hall of the wicked. The psalmist evokes different ways to catch the contagion of cruelty: through words, through actions, through the subtle influence of bad company. Through this threefold reprise, the psalmist expands on the concrete particulars through which moral turpitude might arise (and tempt) in daily life.

In this exhibit, the rhythm and aesthetic of repetition-with-variation works on three levels. It describes biblical poetry. It illuminates three of the pieces in this exhibit—those by Borshevsky, Hechle, and Verbeek—which render a biblical Hebrew verse. Hechle and Verbeek even repeat the same line several times, performing it with variations to find new nuances in the words. More broadly, the aesthetic of repetition-with-variation describes the unique beauty of calligraphy itself.

Borshevsky, Hechle, and Verbeek each employ repetition with variation in different ways. Borshevsky only writes his verse once, but his verse fits parallelistic form perfectly:

The righteous flourish like the palm tree,

and grow like a cedar in Lebanon. (Ps 92:12)

In this verse, the second line echoes the first. Indeed, the second line intensifies the first, a common tactic in biblical poetry. The basic metaphor—‘The just shall flourish like a strong, deeply-rooted tree’—moves from palm trees to cedars. While both trees are known for longevity and height, the cedar of biblical times grew taller and lived much longer than the date-palm. Borshevsky similarly intensifies his visual treatment of “and grow like a cedar in Lebanon” by adding more decoration to the letters—in this case, the tagin, or ‘crowns’ (keterim), small decorations added to the tops of specific letters in the specific Hebrew script used for holy writings (stam script). The ‘crowns’ on these letters echo the cedar’s royal and sacral associations, as they were used to build both the Temple and Solomon’s palace.

Hechle and Verbeek take a different tack. Each of them writes the same line repeatedly, but ‘performs’ it in different voices and visual intonations.

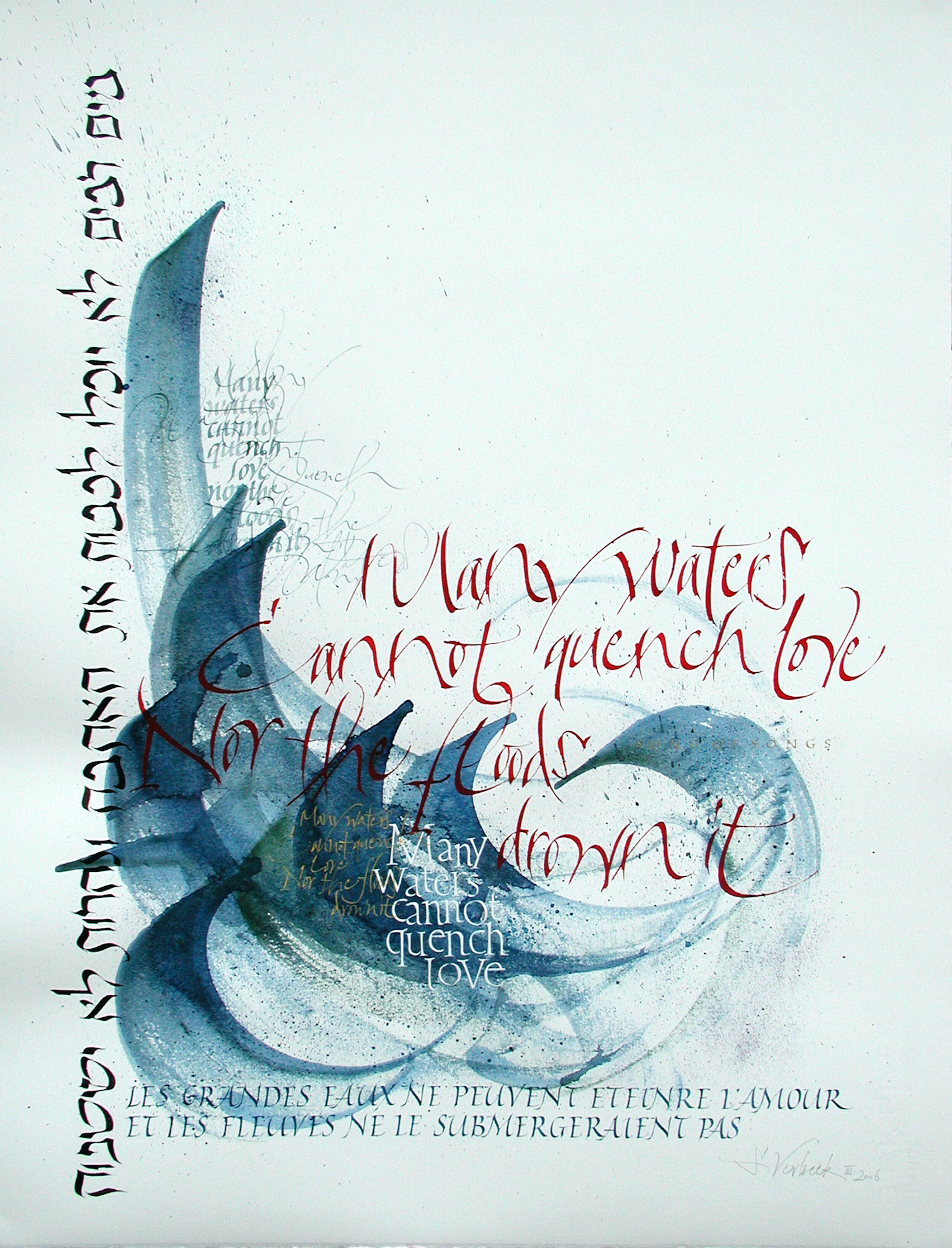

Verbeek’s work repeats a pivotal line from the Song of Songs, ancient Israel’s love poetry:

Many waters cannot quench love,

neither can floods drown it. (Song 8:7a)

She renders the line seven times, in English, Hebrew, and French, exploring different visual possibilities by employing both formal and gestural writing styles. The formal ones, such as the French at bottom or the white serifed line in the middle, evoke the might, the quality of being upright, of the unquenchable flame of love. They visually contrast with the more formal, expressive repetitions, such as the vertical Hebrew at left or the large red rendition in the middle. These evoke the movement of the waters, the vigor of love’s passion.

While Verbeek repeats the line with varied gesture and movement, Hechle varies the line breaks, letter weights, and word sizes in her series of variations on a line from the Psalms:

Be still then and know that I am God. (Ps 46:11)

Hechle chose this line for its many nuances. Does God speak it with impatience or encouragement—that is, is the hearer afflicting or afflicted? Is the emphasis on “still” or “know”? What is the relationship between being still and knowing the presence of God? In some variations, Hechle adds space between “then” and “know,” suggesting a pause; but how long must we wait to know? As the psalmist would say: How long, O Lord?

Hechle and Verbeek’s mode of repetition-with-variation parallels an actor rehearsing her lines repeatedly, trying to find the right way to deliver it. But while the actor can only speak her line in one way in each performance, the calligrapher can repeat it many times on the simultaneity of the page. The calligrapher, then, is more like a choral composer setting text to music, especially to counterpoint. A contrapuntal composer, like Bach, repeats the same line many times for different emphases and effects. (This analogy is explored more in Lucinda Mosher’s thematic essay.) All three—actor, calligrapher, choral composer—do not merely represent words. They perform them, and each performance is unique.

As an aside, one might imagine a whole other form of repetition-with-variation. Scholars of the Bible are well aware of what gets lost in translation. Every translator must choose which aspects of the source text to keep, and which to leave behind. Imagine, then, a calligraphic exploration of the Psalms which juxtaposes several translations. Each rendering could convey different wordplays, different shades of meaning, in the Hebrew:

“Be still and see that I am God;” (Douay-Rheims)

“Let go, and know that I am God.” (Alter)

“Relax, and know that I am God!” (NETS)

“Slacken! And acknowledge! that I am God” (Cook)

Even if the words are mostly the same, the translator’s choice of punctuation can impact the oral volume and emotional tone of the line:

“Be still, then, and know that I am God;” (1979 Book of Common Prayer)

“Be still, and know that I am God:” (KJV)

“Be still, and know that I am God!” (NRSV)

“Be still and know that I am God,” (Revised Grail Psalter)

Varied repetition in music: “Be still and know that I am God.”

Imagine a page with these translations in parallel, in different shapes and weights, allowing the reader to ponder many dimensions of the line. The point is not to find the ‘correct’ translation, but to see the manifold possibilities of translation, both what gets lost and what gets added.

Finally, the aesthetic of repetition-with-variation also describes the letter artist’s work. Unlike the cold mechanical perfection of type, in which every letter is identical, the calligrapher’s page of writing will never reveal exactly the same ‘a’ or ‘S’ or ‘y’. The master scribe may aim for perfect letters, but this is neither humanly possible nor aesthetically desirable. In this art ‘perfection’ is not uniformity but harmony. Each ‘a’ must harmonize with every other ‘a’. The letters must live well together as words; letters alone mean nothing. The words must harmonize with the blocks of text, which in turn must fit into the overall design and the page. Hechle’s work provides a perfect example: the proportions, the skeletons, of each of her capital letters are based on the Roman heritage, but no two look exactly the same. For the scribe, variation, even mistakes, give a work the human touch.

However, as the wild contrasts of Verbeek’s work remind us, what harmony looks like can vary immensely. Clashes can still occur within harmony.

If biblical poetry is repetition-with-variation, then so is calligraphy. Looking at a well-made page of calligraphy reveals the subtle differences between each ‘a’ and ‘S’, which is one of this artform’s visual joys. Diane von Arx’s calligraphic rendering of the poem “The Windhover” shows this well: the flourished top of each ‘d’ and bottom of each ‘g’ differs from its counterparts. Each suggests the fun of freedom. But each is made with the thoroughness of discipline. A wild, playful flourish will not redeem a shoddy, sloppy letter. Von Arx exemplifies a common motto for calligraphic art: “disciplined freedom.” Both are required. Without discipline, nothing is possible: driving a car, using a tool. But without freedom, we are merely mechanical parrots repeating perfect shapes. Each ‘g’ represents these two paradoxes: disciplined freedom and varied repetition.

Finally, both calligraphic and poetic repetition invite our own voice. Will we ever exhaust the possible variations of the letter ‘a’, or the emotional shades of “be still and know that I am God”? I think not. After we have read the poem, after we have viewed the textual art, we can pick up our own pens. We write our own letter ‘a’, striving for perfection along the way. We make the Psalms our own, rehearse their ‘emotional scripts’, inhabit their inner resonances through the prisms of their own lives. And we—both calligraphers and readers of sacred texts— learn and grow best in community.

Jonathan Homrighausen, a doctoral student in Hebrew Bible at Duke University, explores the intersection of biblical literature and its reception in the arts—especially calligraphy and lettering arts. He is the author of Illuminating Justice: The Ethical Imagination of The Saint John's Bible (Liturgical, 2018), Set Me as a Letterform: The Saint John’s Bible, the Song of Songs, and The Word Made Flesh (Liturgical, forthcoming), and articles in Religion and the Arts, Image, Teaching Theology and Religion, Transpositions, and Visual Commentary on Scripture. He is currently preparing a dissertation on Esther scrolls, visual storytelling, and the meanings of writing.

Further Reading:

On biblical Hebrew poetry in general, see Robert Alter, The Art of Biblical Poetry, rev. ed. (New York: Basic Books, 2011); F. W. Dobbs-Allsopp, On Biblical Poetry (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015).

My thinking on the Psalms is heavily influenced by Ellen F. Davis, Wondrous Depth: Preaching the Old Testament (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2005), chap. 2, “Maximal Speech: Preaching the Psalms.” I borrowed the phrases “repetition-with-variation” and “emotional script” from her.

My understanding of performance derives from David Rhoads, “Performance Criticism: An Emerging Methodology in Second Testament Studies,” Biblical Theology Bulletin 36, no. 3 (August 1, 2006): 118–33, and 36, no. 4 (November 1, 2006): 164–84. The analogy with actors rehearsing lines was first suggested to me by Megan M. Wines.

On performance traditions of the Psalms, see Joshua R. Jacobson, “The Cantillation of the Psalms,” Journal of Synagogue Music 39 (2014): 17–34; Joshua R. Jacobson, “Decoding the Secrets of the Psalms,” The Choral Journal 56, no. 7 (2016): 20–31; John D. Witvliet, The Biblical Psalms in Christian Worship: A Brief Introduction and Guide to Resources (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2007).

Lesser-known Psalm 46:11 translations from Ryan Cook, “Prayers That Form Us: Rhetoric and Psalms Interpretation,” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 39 (2015): 459; Robert Alter, The Hebrew Bible: A Translation with Commentary (New York: W. W. Norton, 2018), 3:123; Gregory J. Polan, ed., The Psalms Songs of Faith and Praise: The Revised Grail Psalter with Commentary and Prayers (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 2014), 110.

I have learned much about harmony in calligraphy from John Stevens, Scribe: Artist of the Written Word (Greensboro, NC: John Neal Books, 2013); Ann Hechle, In the Beginning: A Journey into Meaning through the Making of a Calligraphic Work (self-published, 2020). The phrase “disciplined freedom” comes from Raymond DaBoll (1892–1982), who coined it for a famous 1948 poster on calligraphy; see image in Dorothy E. Miner, Two-Thousand Years of Calligraphy (Totowa, NJ: Rowman & Littlefield Pub Inc, 1980), cat. no. 159. Further reflections on the subject are in Lloyd J. Reynolds, “Comments on Disciplined Freedom,” in Straight Impressions (Woolwich, ME: TBW Books, 1979), 26–28; Sheila Waters, “Calligraphy in the Pursuit of Excellence” (lecture given to the Washington Calligraphers Guild, August 6, 1988).